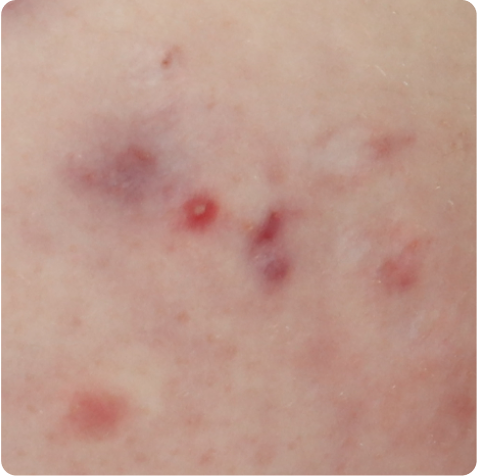

Hurley Stage II (moderate):

Abscesses recur and develop fistulas or sinus tracts that can release malodorous, purulent discharge

This site is intended for US healthcare professionals | PATIENT SITE

Actual patient living with HS

A delayed HS diagnosis can lead to missing the window of opportunity for early treatment and make the patient nightmare even longer and more frustrating. It’s physically and mentally exhausting. By the time a diagnosis is received, patients with HS have often seen numerous providers—all while suffering the relentless torment of painful skin lesions and fighting an ongoing sense of despair.1-3

A diagnosis of HS is based on the following clinical criteria3,4:

Tunnels are openings at the skin surface that can drain malodorous fluid.3

Axillae

Inframammary

Crural folds

Typical locations include axillae, inframammary areas, and crural folds. HS may also occur less

frequently in other locations, including the lower abdomen, scalp, neck, and eyelids.5

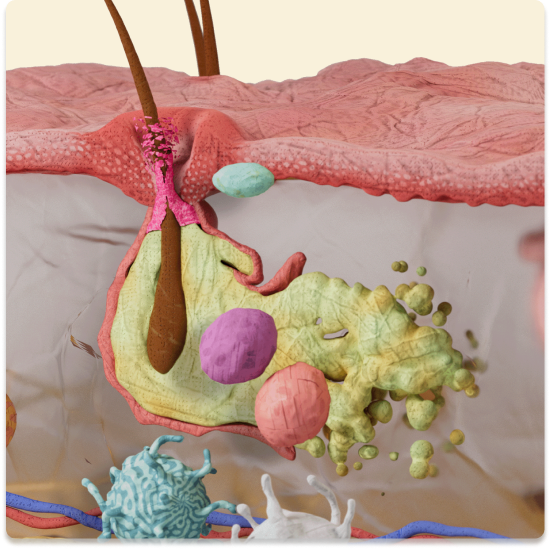

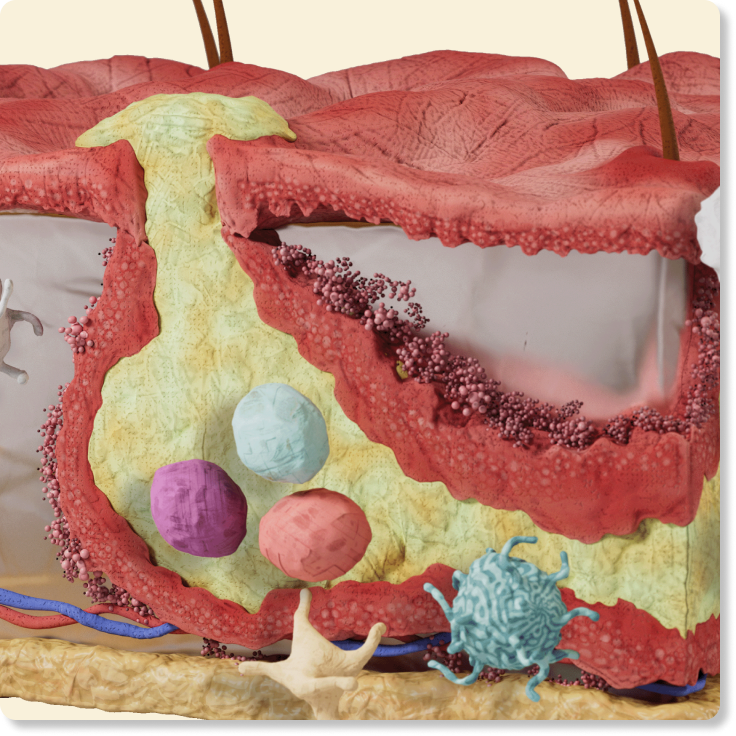

Often mistaken for infection, HS is a diagnosis of exclusion. It typically starts with the formation of single or multiple abscesses and gets progressively worse. The intertriginous areas–axillae, inframammary areas, and crural folds–are the most commonly affected sites in adults. While biopsies and cultures are not routinely recommended, a biopsy may show hyperkeratosis of a hair follicle while cultures are usually negative. Lesions may test positive, however, for Staphylococcus aureus during flares.6 Exceptions to these rules include cases where HS occurs in adolescents and children.7

Folliculitis

Furuncle

Carbuncle

nodules, abscesses, purulent discharge

primarily caused by an infection, random distribution, burning, and perilesional erythema

Back acne

Hyperpigmentation

Acne scarring

cysts with pus, inflammatory nodules, scars

varying distribution compared to HS (face, back, upper chest)

localized to genital and inguinal folds

red ulcers, granulation of tissues, easily bleeds, infectious disease

Abscesses recur and develop fistulas or sinus tracts that can release malodorous, purulent discharge

Formation of single or multiple, painful, inflamed nodules or abscesses

Inflamed skin is severely damaged; diffuse involvement of large areas with multiple abscesses and interconnected sinus tracts, as well as significant scarring

Hurley Staging is considered the most commonly used severity classification. 70% of patients have mild HS (Hurley Stage I) and 30% of patients have moderate-to-severe HS (Hurley Stages II and III).12

A delayed diagnosis together with multiple misdiagnoses, mismanaged care, and inappropriate treatments contributes to disease progression and poor outcomes.3

Delays can also lead to greater disease severity at the time of diagnosis and a greater number of surgically treated sites, concomitant diseases, and work-related disruptions.2

While Hurley Staging is the first (1989) and best-known clinical scoring system used for HS, a number of other scoring systems have since been established. These include but are not limited to13:

2003 Sartorius Score

2010 HS Severity Index (HSSI)

2012 HS-Physician Global Assessment (HS-PGA)

2012 Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Score (HiSCR)

2017 International HS Severity Scoring System (IHS4)

2019 HS Area and Severity Index (HASI)

An assessment of a patient’s disease severity or response to treatment can vary depending on which clinical scoring is used.13 Therefore, in some cases, it may be appropriate to use several measures to determine a patient’s disease severity.13

of patients visited a physician for HS symptoms more than 5 times before an appropriate HS diagnosis was made.14

A delayed diagnosis markedly contributes to disease progression, comorbid conditions, and an increased number of surgically treated sites.2,3

The average time from symptom onset to HS diagnosis is 10 years,14 with more than 3 misdiagnoses along the way.2

Based on a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the rate of hospitalizations with HS as a primary diagnosis increased from 7.9 per 100,000 all-cause hospitalizations in 2008 to 11.6 per 100,000 all-cause hospitalizations in 2017 (P<0.0001).15

Characterized by boils and skin scarring, HS is often misidentified as more well-known skin conditions, such as acne vulgaris or folliculitis. Because of this, it can take years for a patient with HS to receive a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.2

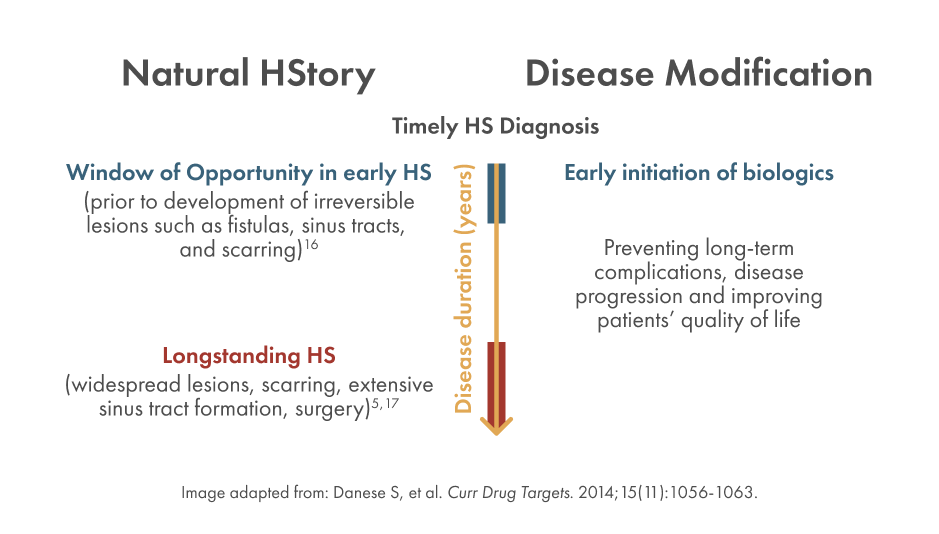

Addressing HS early, when anti-inflammatory attempts will be most effective, can decrease disease progression and may alter the natural HStory of the disease.16 This window of opportunity is the optimal time for treating HS and improving clinical outcomes, before irreversible damage and development of lesions such as fistulas, sinus tracts, and scarring.11,16

HS of the axillae with a visible, boil-like nodule.

Close-up of HS on the thigh, showing red, swollen boils/lesions.

HS lesion on the face.

HS lesion in the anogenital area.

HS of the axillae showing characteristic inflammatory nodules and scarring.

Axillary HS with an abscess, inflammatory nodules, and scarring.

HS of the abdomen with inflammatory nodules, nondraining tunnels, and scarring.

Inguinal HS with inflammatory nodules, nondraining tunnels, and scarring.

HS of the axillae with an abscess, inflammatory nodules, and scarring.

Inguinal HS with multiple inflammatory nodules, draining tunnels, and scarring.

HS of the breast fold with multiple abscesses, inflammatory nodules, draining tunnels, and scarring.

HS of the buttocks with tunneling and scarring.